In Brasilien und auch im Ausland hört man führende Persönlichkeiten des brasilianischen Agrarsektors in ihren Reden öfters sagen: „Brasilien ist das Land mit den restriktivsten Umweltgesetzen der Welt“. Die Absicht ist, die brasilianische Agrarproduktion als ökologisch nachhaltig darzustellen und rechtfertigen. Sie wollen den Eindruck erwecken, dass unser natürliches Erbe durch den Agrarsektor, derjenige, der den Boden intensiv nutzt und für den Großteil der Exporte des Landes verantwortlich ist, in guter Pflege ist.

Es stimmt, Brasilien hat eine Reihe von Gesetzen zum Schutz der natürlichen Ressourcen, angefangen mit dem Waldgesetz. Diese gesetzlichen Bestimmungen wurden gleichzeitig zum Schutz des Bodens, der Gewässer, der Kohlenstoffspeicherung, der Holzproduktion, der biologischen Vielfalt und der Lebensgrundlage der Menschen, die im Wald, vom Wald und für den Wald leben, wie z. B. indigene Völker, Kautschukzapfer, Nusssammler und andere konzipiert.

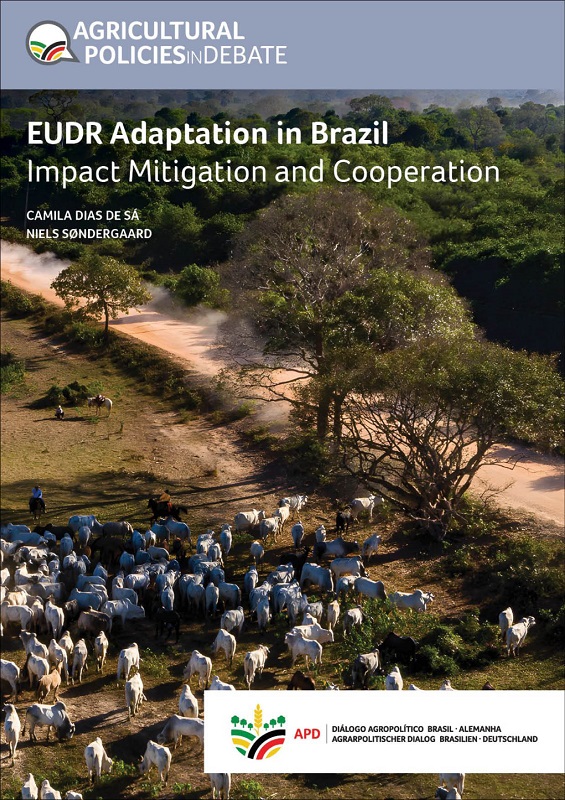

Es ist allerdings auch Tatsache, dass Weideland und landwirtschaftliche Flächen in zunehmender Weise Wälder verdrängen. Dies wird von offiziellen und nicht offiziellen Systemen zur Entwaldung und Waldschädigung erfaßt. Die alarmierenden Entwaldungsraten schockieren die ganze Welt.

Beide Seiten zusammenzuführen und mit der Tatsache zu vereinbaren, dass Brasilien sich zunehmend als wichtiger Nahrungsmittelproduzent positioniert – für eine Welt im Klimawandel – das ist die große Herausforderung. Diese muss bewältigt werden von Unternehmern, Führungskräften und Politikern mit einer klaren Zukunftsvision, die sich um das Wohlergehen der Gesellschaft kümmern und die Chancen einer neuen Realität nutzen. Der Klimawandel verändert bereits die landwirtschaftlichen Produktionsstandards wie auch den Konsum auf der ganzen Welt.

Wenn wir diese große Herausforderung in kleinere Teile auftrennen, zeigt sich eine wichtige Komponente: die Notwendigkeit, die vollständige Rückverfolgbarkeit der brasilianischen Agrarprodukte zu gewährleisten. Dies ist die erste Komponente zum Nachweis der ökologischen Nachhaltigkeit der zu exportierende Produkte. Ohne Rückverfolgbarkeit wird es nicht möglich sein, denjenigen eine Antwort zu geben, die die Fähigkeit des brasilianischen Agrarsektors in Frage stellen, eine Produktion zu tätigen, ohne die natürlichen Ökosysteme des Landes zu zerstören und dadurch den Klimawandel des ganzen Planeten beeinflussen.

Als Beispiel kann die Rinderzucht angeführt werden. Nur ein winziger Bruchteil der produzierten Tiere wird von der Geburt bis zur Schlachtung rückverfolgt. Darunter findet man Rinder, die in einem einzigen landwirtschaftlichen Betrieb bzw. in einem vollständigen Viehzuchtzyklus gezüchtet, aufgezogen und gefüttert werden. Die große Mehrheit der gezüchteten Tiere durchläuft jedoch drei oder mehr Betriebe, bevor sie an die Schlachthöfe geliefert werden. Erst in dem Betrieb, der die Tiere zur Schlachtung verkauft, wird die ganze Betriebsfläche analysiert. Bei dieser Analyse wird geprüft, ob dort die Umweltvorschriften eingehalten werden und ob Teile der Fläche sich nicht mit benachbarten Schutzgebieten wie Naturschutz- oder indigene Gebiete überschneiden.

Ohne Zahlen oder Gesetze zu zitieren, sondern nur auf der Grundlage allgemein bekannter Fakten, wird deutlich, dass umfassende und moderne Gesetze allein nicht ausreichen, zu beweisen, dass Brasilien eine nachhaltige landwirtschaftliche Produktion betreibt. Wir müssen viel weiter ausgreifen und nicht nur zeigen, dass es noch intakte Waldgebiete im Amazonas und Cerrado gibt. Wir müssen zeigen können, dass Unternehmen und Regierungen das Mögliche und Notwendige tun, um das Fortbestehen von Wäldern für die nächsten Jahrhunderte zu gewährleisten. Was wir heute an Fakten und Zahlen haben, führt zu einer pessimistischen Prognose, in der Naturgebiete Jahr für Jahr an Fläche verlieren, bis nur noch die gesetzlich geschützten Gebiete übrigbleiben. Diese Gebiete allein werden nicht das notwendige Niederschlagsregime und die klimatischen Bedingungen schaffen, um die Nachhaltigkeit der brasilianischen Agrarproduktion zu gewährleisten.

Wir müssen sofort damit beginnen, diese Zukunft neu zu gestalten, und wir besitzen die Mittel dazu. Die erste Herausforderung, die wir bewältigen müssen, ist die Verwirklichung der Rückverfolgbarkeit der brasilianischen Agrar- und Viehwirtschaft. Das würde uns in eine günstigere Position zur Verhandlung von internationalen Abkommen wie z.B. das Freihandelsabkommen zwischen dem Mercosur und der Europäischen Union versetzen. Somit wären wir in der Lage, einige Anpassungen der EU-Entwaldungsverordnung (EUDR) zu fordern, gestützt durch das Gewicht eines Landes, das nicht nur viel sondern korrekt produziert!

Weniger als sechs Monate bevor die EU-Entwaldungsverordnung (EUDR) in Kraft tritt, welche 2025 die Einfuhr von Agrarprodukten, die mit der Entwaldung in Zusammenhang stehen, verbietet, gibt es noch eine Reihe von Unsicherheiten.

Weniger als sechs Monate bevor die EU-Entwaldungsverordnung (EUDR) in Kraft tritt, welche 2025 die Einfuhr von Agrarprodukten, die mit der Entwaldung in Zusammenhang stehen, verbietet, gibt es noch eine Reihe von Unsicherheiten.

Die EU-Entwaldungsverordnung (EUDR) zielt darauf ab, die nachteiligen Auswirkungen von EU-Importen auf die globalen Wälder, den Klimawandel und die biologische Vielfalt ab dem 31. Dezember 2024 zu verringern. Sie schreibt eine Sorgfaltsprüfung für Produkte vor, die waldgefährdete Rohstoffe wie Rindfleisch, Kakao, Kaffee, Ölpalmen, Kautschuk, Soja und Holz enthalten, um sicherzustellen, dass sie nicht von kürzlich abgeholzten Flächen stammen.

Die EU-Entwaldungsverordnung (EUDR) zielt darauf ab, die nachteiligen Auswirkungen von EU-Importen auf die globalen Wälder, den Klimawandel und die biologische Vielfalt ab dem 31. Dezember 2024 zu verringern. Sie schreibt eine Sorgfaltsprüfung für Produkte vor, die waldgefährdete Rohstoffe wie Rindfleisch, Kakao, Kaffee, Ölpalmen, Kautschuk, Soja und Holz enthalten, um sicherzustellen, dass sie nicht von kürzlich abgeholzten Flächen stammen.

Die Landwirtschaft spielt eine zentrale Rolle bei der Förderung von Maßnahmen, die zur Verringerung und Beseitigung von Treibhausgasemissionen (Mitigation) und zur Anpassung an den Klimawandel führen, mit dem Ziel, die globale Ernährungssicherheit zu gewährleisten und zu den Klimazielen des Pariser Abkommens beizutragen.

Die Landwirtschaft spielt eine zentrale Rolle bei der Förderung von Maßnahmen, die zur Verringerung und Beseitigung von Treibhausgasemissionen (Mitigation) und zur Anpassung an den Klimawandel führen, mit dem Ziel, die globale Ernährungssicherheit zu gewährleisten und zu den Klimazielen des Pariser Abkommens beizutragen.

Dieses Dokument bietet einen Überblick über die Agrarökologie in Brasilien, von ihren historischen und konzeptionellen Grundlagen bis hin zu den neuesten Techniken und Technologien.

Dieses Dokument bietet einen Überblick über die Agrarökologie in Brasilien, von ihren historischen und konzeptionellen Grundlagen bis hin zu den neuesten Techniken und Technologien.

Dieser Artikel beschreibt die Umsetzung von unternehmerischen Sorgfaltspflichtinitiativen in der Europäische Union (EU) und bezieht dabei auch aktuelle wissenschaftliche und politische Diskussionen ein.

Dieser Artikel beschreibt die Umsetzung von unternehmerischen Sorgfaltspflichtinitiativen in der Europäische Union (EU) und bezieht dabei auch aktuelle wissenschaftliche und politische Diskussionen ein.

Dieses Jahr, am 30. Dezember, tritt die Europäische Entwaldungsverordnung (EUDR) in Kraft. Ziel dieser Verordnung ist die Sicherstellung entwaldungsfreier Lieferketten für landwirtschaftliche Produkte, die sich in der Vergangenheit als starke Treiber der globalen Entwaldung erwiesen haben. Im Einzelnen erstreckt sich die Regulierung auf die Bereiche Soja, Palmöl, Gummi, Kakao, Kaffee, Rinderzucht und Holzgewinnung. Unmittelbar betroffen von der EUDR sind Unternehmen mit Sitz in der Europäischen Union (EU), wenn sie eines der genannten Produkte in den Verkehr des EU-Binnenmarktes bringen. Im Kern verpflichtet die EUDR diese „Inverkehrbringer“ dazu, ihre Transaktionen im Vorfeld zu registrieren sowie eine umfangreiche Sorgfaltspflichterklärung abzugeben. Zentraler Bestandteil der Sorgfaltspflichten sind Angaben zum genauen Produktionsort der in den Markt gebrachten landwirtschaftlichen Erzeugnisse basierend auf satellitengestützten Geolokationsdaten.

Dieses Jahr, am 30. Dezember, tritt die Europäische Entwaldungsverordnung (EUDR) in Kraft. Ziel dieser Verordnung ist die Sicherstellung entwaldungsfreier Lieferketten für landwirtschaftliche Produkte, die sich in der Vergangenheit als starke Treiber der globalen Entwaldung erwiesen haben. Im Einzelnen erstreckt sich die Regulierung auf die Bereiche Soja, Palmöl, Gummi, Kakao, Kaffee, Rinderzucht und Holzgewinnung. Unmittelbar betroffen von der EUDR sind Unternehmen mit Sitz in der Europäischen Union (EU), wenn sie eines der genannten Produkte in den Verkehr des EU-Binnenmarktes bringen. Im Kern verpflichtet die EUDR diese „Inverkehrbringer“ dazu, ihre Transaktionen im Vorfeld zu registrieren sowie eine umfangreiche Sorgfaltspflichterklärung abzugeben. Zentraler Bestandteil der Sorgfaltspflichten sind Angaben zum genauen Produktionsort der in den Markt gebrachten landwirtschaftlichen Erzeugnisse basierend auf satellitengestützten Geolokationsdaten.

The 2022 Deforestation Regulation of the European Union marks a significant stride in combating deforestation within commodity supply chains. Nevertheless, the compliance requirements for traceability and transparency have left many policy makers and corporations in producer and importer countries in confusion. In the context of Brazil, two key exported commodities affected by this legislation are soy and cattle products, of which a substantial part reaches the borders of the EU.

The 2022 Deforestation Regulation of the European Union marks a significant stride in combating deforestation within commodity supply chains. Nevertheless, the compliance requirements for traceability and transparency have left many policy makers and corporations in producer and importer countries in confusion. In the context of Brazil, two key exported commodities affected by this legislation are soy and cattle products, of which a substantial part reaches the borders of the EU.